A gigantic work in every respect

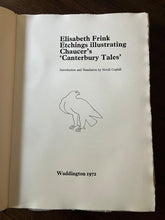

FRINK, Elisabeth (illustrator); Geoffrey CHAUCER, trans. Nevill COGHILL. Etchings illustrating Chaucer's 'Canterbury Tales'. London: Leslie Waddington Prints. 1972.

Elephant folio. Original green cloth with blocked bird illustration in gilt to front cover with gilt lettering to spine; pages untrimmed; unpaginated with 19 full page etchings; spine a little rubbed with a tear at rear and bruised at head; spine at a slight lean; otherwise a near fine copy.

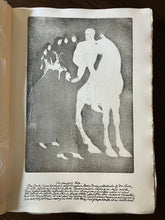

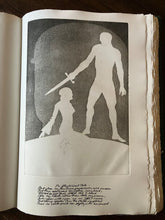

An exceptionally rare and phenomenal rendition of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, resplendent with animals, birds and mythical characters by the renowned English artist and printmaker Elisabeth Frink.

Frink's nineteen full page etchings provide illustration for all of the following from the Middle English classic: The Prologue, The Knight's Tale, The Miller's Tale I, The Miller's Tale II, The Reeve's Tale, The Shipman's Tale, The Prioress's Tale, Chaucer's Tale of Sir Topaz, The Nun's Priest's Tale, The Physician's Tale, The Pardoner's Tale, The Wife of Bath's Tale, The Summoner's Tale, The Clerk's Tale, The Merchant's Tale, The Squire's Tale, The Franklin's Tale, The Second Nun's Tale and The Manciple's Tale.

One of the most revered female twentieth-century artists, Elisabeth Frink was a true Post-War thinker - her famous sculpture works and etchings predominantly revolve around archetypes of masculine aggression, rarely working with the female form, and her challenge of the perception of war liken her to contemparies like Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth. As did Hepworth, she found her stature in an era in which sculpture remained a male domain. Coinciding with the production of this beautiful artistic translation of Chaucer was her Goggled Heads , a series of sinister male faces, of which she commented; 'The soldiers' heads were started in 1964 in England and led on to the goggle heads, which were the reflection of my feelings about the Algerian War and the Moroccan strongmen. One, called Oufkir, was held largely responsible for the death of the Algerian freedom fighter Ben Barka. Oufkir had an extraordinarily sinister face - always in dark glasses. These Goggle Heads became for me a symbol of evil and destruction in North Africa and, in the end, everywhere else'.

Similar to the mastery of Moore, Frink was distinct in her practice - casting from an original model that was built up with plaster, then hacking back at the plaster with a chisel. This refuted the methodology of canonical names such as Rodin. Not only did she focus on men, "I have focused on the male because to me his is a subtle combination of sensuality and strength with vulnerability", but she made mythical horses and birds her other primary subjects- an allegiance which is exemplified in her illustrations for Aesops Fables. She was also responsible for the illustrations of a version of The Odyssey, also published by Leslie Waddington. The spirit and frequent humour of Chaucer's characters are illuminated by Frink's preference for the naturalistic, for capturing the spirit, rather than the strict human bodies, of the stories.

She was lauded as prodigy at the age of twenty-two when, as she finished her studies at Chelsea School of Art, a major exhibition at The Beaux Art Gallery in 1952 led to The Tate Gallery purchasing her work Bird . This rare limited edition casts in spectacular condition the delicacy of an imagination otherwise known commonly for its masculine encounter with bronze.

#2120582