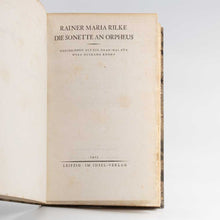

RILKE, Rainer Maria Sonette an Orpheus Leipzig: Im Insel-Verlag. 1923.

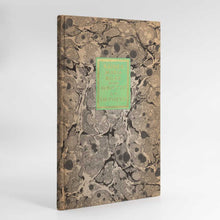

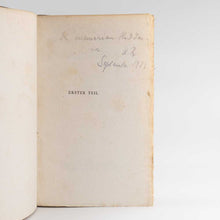

8vo. Original marbled paper-covered boards, green paper inlay lettered and framed in gilt to front board; pp. 63, [1]; light rubbing to extremities of boards, mild spotting and staining throughout (though less than usual with this volume), wrapper a touch frayed to upper edge of front panel; a near fine copy, in like dustwrapper; contemporary pencilled inscription to the title page preceding the Part I: “In memoriam Hiddensee. / R. B. / September 1923” (Hiddensee, the island resort in the Baltic sea, located west of Rügen on the German coast).

An uncommonly bright, sharp copy of the first edition of Rilke’s swan song, in a startlingly fresh example of the scarce dustwrapper, and with an intriguing contemporary inscription.

Rilke’s sequence of 55 Sonnets to Orpheus came as a late and unexpected flowering after a period during which the poet was unable to write. “These strange Sonnets,” Rilke wrote in the year of publication, “were not intended or expected; they appeared […]. I could do nothing but surrender, purely and obediently, to the dictation of this inner impulse.” He had begun writing the Duino Elegies in 1912, but a combination of private and personal circumstance (the approaching war uppermost) led to a depressive illness which postponed their completion for nearly a decade. In 1921, Werner Reinhart invited Rilke to stay at the Château de Muzot near Veyras in the Rhone Valley, and it was there that news arrived of the premature death of Wera Knoop, (1902–21), daughter of his friend Gerhard Ouckama Knoop and childhood playmate of his own daughter Ruth. She was 19 years old. The news unexpectedly galvanised the poet, prompting the composition of the first 26 Sonnets to Orpheus (reportedly in three days), the completion of the long gestating Elegies, followed by the remaining 29 Sonnets (the Elegies and Sonnets , according to Rüdiger Görner, constitute the “pinnacles of Rilke’s poetic achievements, [and] twin peaks of German poetry in the twentieth century”).

Famously allusive (and elusive), the figures of Orpheus and Eurydice permeate rather than dictate the sequence, the titular Orpheus acting “as an agent of transition and transformation” (Görner) in poems where instability, metamorphosis, and the connection of seeming opposites – life/death; nature/culture – is paramount.

Since the 1930s, and J. B. Leishman’s first rendering of the Orpheus sonnets (published by Virginia and Leonard Woolf at The Hogarth Press), they have led a parallel life in English, most recently in a series of resonant versions “after” Rilke’s originals by the Scottish poet, Don Paterson, in 2006.

Hiddensee, mentioned in the contemporary pencilled inscription inside this copy, had become a fashionable resort during the period of hyperinflation affecting the German Mark between 1921 and 1923 (and peaking in November 1923), holidays abroad having become unaffordable. The crisis hit the German middle classes hardest and was clearly instrumental in fomenting far right, populist political rhetoric and the inexorable rise of the National Socialist Party.

See: Karen Leeder and Robert Vilain (eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Rilke (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Hünich p.92; Ritzer E46; Sarkowski 1357.

#2122306